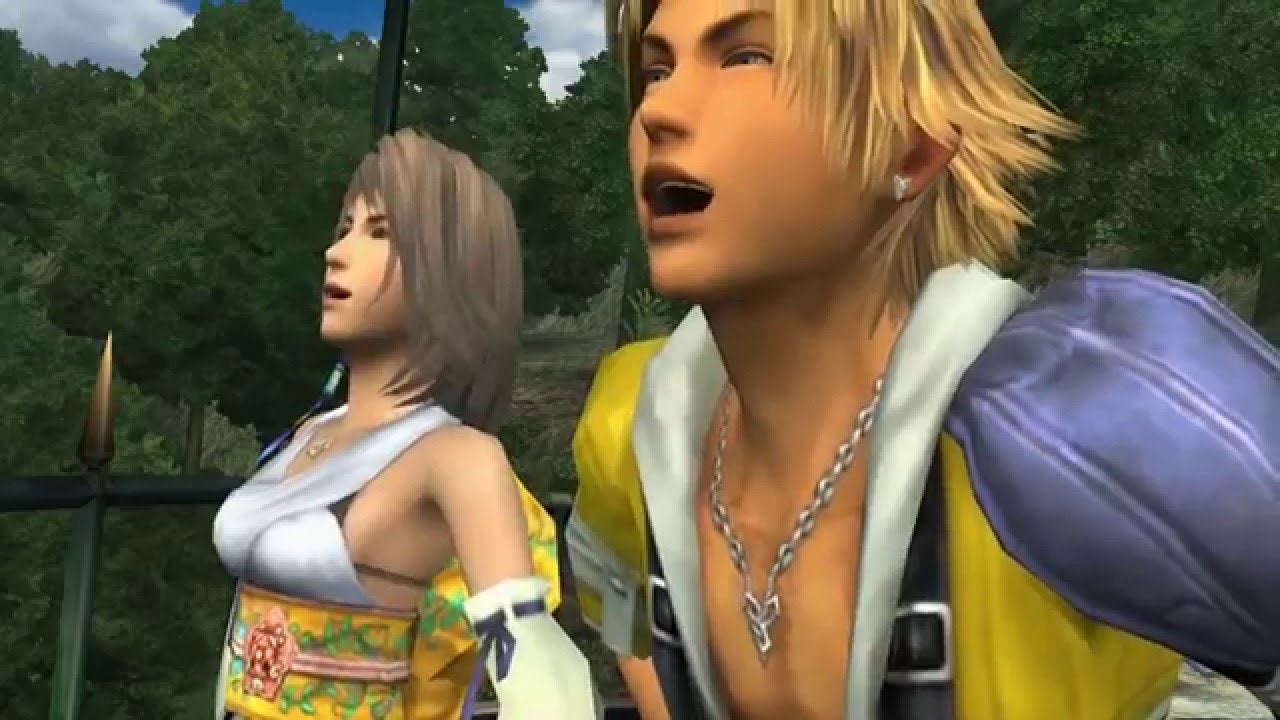

The computer-controlled king also takes his turn. By day, he sends the royal guard to defend or tyrannise the kingdom, and picks favourites from among the players - whoever is leading on Prestige gets to pass a law, such as a ban on magic. By night, the king’s corruption spreads to infest map tiles with hideous winged demons. There are three routes to victory: amass the most prestige, defeat the king hand-to-hand before he succumbs to the Rot, or gather enough spirit stones to assume the mantle of healer, allowing you to cleanse your ailing lord and send him peacefully to the afterlife. The journey will be eventful either way, the balance of hero stats and the whim of RNG telling a fresh story each time. But there is only ever one final outcome: the king will die. I began playing Armello a few months after my sister Bea was diagnosed with cancer in late 2018. She passed away a few weeks ago. I’ve spent most of the intervening time caring for her at the family home, along with my dad, my other sister and my disabled brother. Bea and I played many videogames together, she and I being the geeks of the household. Armello wasn’t one of these games: it felt too close to the bone, not that Bea had many qualms during her illness about games in which mortality is the major theme (among those she picked for the whole family to try were Until Dawn, The Walking Dead and What Remains of Edith Finch). But I’ve found Armello a useful way of thinking about our situation - and about how playing a videogame for someone can be an act of care. Rather than usurpers, I think of Armello’s heroes as embattled caregivers, staging one last, outrageous courtly intrigue for the king as his sickness progresses. Wolf beats rabbit with enchanted axe, rabbit lures rat into magic bog, rat hires wandering circus to steal rabbit’s best spell, which he uses to curse wolf with selenophobia… The cards and dice rattle together; the heroes strut about pushing each other down flights of stairs and getting into spats with the palace enforcers; the lion cackles away on his throne at the heart. This article isn’t a claim for some special status for videogames as means of therapy. Frankly, my time with my sister has left me with renewed loathing for the investment of hours and days videogames often demand in return for the mediocre enjoyment of, say, blowing somebody’s head off in a “satisfying” way, or dragging out a theme any half-inspired short story writer could accomplish in a couple of paragraphs. When videogames are bad they are the worst kind of art, produced at great cost to their creators and the planet, and made up of poorly dramatised, habit-forming busywork plugged into hollow, binary-coloured simulacra of broken value systems and still-active legacies of bloodshed and exploitation. I am angry to think of Bea feeding her remaining afternoons and evenings to games like Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, or the later Far Cries - games that have redeeming qualities, but which hinge on repetition, scale and conquest for its own sake. I am angry that she often had no choice but to distract herself with such things while she was relatively mobile, thanks to the burden of self-isolation placed on the vulnerable by the Tory government’s unforgivable early decision to allow Covid to spread unchecked. But it wasn’t and isn’t my place to lecture Bea about how she spent her time, and besides, even a “bad” game can be uplifting if it’s played for company. Playing a videogame for someone is a far more elaborate skill than just playing to win. A videogame is primarily an expressive tool, even if the audience is simply the player herself. It requires a knack for framing, pacing, a certain stage presence, not just dexterity and strategy but an understanding of what abilities and systems say - or what they can be made to say, by tugging against the developer’s intent and constraints. It is about telling yourself a story, acting a world out, as wittily as you can manage. When playing for another, it requires an awareness of their tastes and sensitivities. Bea greatly enjoyed gossipy RPGs, for instance. She liked being the invisible fifth party member during my time with Dragon Age: Inquisition - listening to Vivienne and Dorian bitch about Skyhold’s wine while out on manoeuvres, or flinty Cassandra wrestle with Cole’s enigmas, or Sera get under everybody’s skin. She liked mocking, then falling in love with the cringy, over/under-dressed characters of anime epics like Tales of Arise. Mind you, she didn’t want to hear everything the Tales cast had to offer - I learned to skip the optional manga-style “skits” that accrue as you explore, which are sometimes little more than glorified tutorial entries. Bea shared my love of eldritch realms, but she didn’t relish being pounced upon by their denizens. With games like Little Nightmares 2, Subnautica: Below Zero and Amnesia: Rebirth, I was essentially her way of interrogating a ghastly universe from a safe remove, a UAV she’d deploy to roam the depths (not that I was just a transparent interface - part of the fun, of course, was watching her older brother have a meltdown whenever he opened the wrong door). We also shared a love of garrulous villains. Bea was a late convert to the cult of GLaDOS, Portal’s bumbling, spiteful, musical AI nemesis. The great virtue of GLaDOS from an audience’s perspective is that she will not shut up - each room puzzle is an opportunity for another awkward burn, deepening the mystery of the facility you’re escaping. Sometimes, though, no story or characterisation elements were needed. I challenge anybody not to be mesmerised by the first level of Tetris Effect, even if you’re not holding the controller. We played some of these games in the young person’s cancer ward at the brilliant St James’s Hospital in Leeds, whose Bexley Wing resembles an ark from some Silver Age sci-fi book cover, sailing against colourless November skies. Bea’s room came equipped with a PS4, and I brought in my Switch with a truckload of JRPGs installed. Together, we relived the infamous Tidus laughing scene from Final Fantasy X - an often-lampooned moment which I scorned when first I played the game as an edgy teenager, but which I now read more generously as mechanical anguish born of an inability to express the shock of a world that has changed beyond understanding. I was hoping we might make it all the way to Final Fantasy X-2, whose mid-battle wardrobe changes rank among the series’ most entertaining lightshows. Even if Bea wasn’t watching me play I would keep up a background monologue while she busied herself with painting or various Reddit rabbit holes or writing letters to friends. I sank my teeth into 4X games and waffled on about breakthroughs and setbacks (Bea at one point discreetly Instagrammed me congratulating myself about a fancy kind of destroyer I’d invented in Stellaris). I read out pieces of lore from Sunless Skies and spoke reverentially of Disco Elysium, which Bea eventually tried and wasn’t that impressed by. Much of this was, at most, a minor distraction and a means of occupying my mind while keeping Bea company, of darting around the subject of treatment and prognosis. Probably, a lot of it was unwanted. When somebody is struggling to breathe or keep food down, there’s not much you can do by expounding on the flaws of Resident Evil: Village. Again, this isn’t a rigid argument for the clinical and consolatory value of videogames in themselves, even those that are explicitly concerned with the player’s mental health. It’s more an invitation to think of games as potentially useful, given a considerate player, within the wider practice and profession of caring - an enormously complex role that is both fundamental to our society’s wellbeing and too-often disparaged or condescended to as a “calling” for women who lack the brains and ambition for proper careers. It’s also, I guess, an invitation to think about the performance anxiety that colours the profession of playing games for an audience online. Streaming can be bruising work, even if you’re a cisgender white male. From the perspective of an older “trad” journalist who has barely ever pivoted to video, being an aspiring Youtuber sounds like absolute hell. Having to be on air for as close to 24-7 as possible, having to establish and maintain a persona for clingy fans, having to skill-up relentlessly for trolls and pedants who treat the tiniest misstep as grounds for abuse… So much Let’s Play commentary seems to consist of faux-jolly excuses for these “mistakes” to pre-empt being kicked around in the chat, or having your fumbles recorded and shared on Twitter. I find it difficult to watch Twitch streams because even the low-key sessions, the ones held just for friends with a single digit audience, seem charged with this urge to apologise and deflect. What if we thought of playing games as a careful act, rather than a skilful one, whether we’re playing for others in a professional context, or by ourselves? It’s an idea I’ve tried to put into practice during hands-on events (remember those?) with developers present. When I play an unfinished game with one of its creators watching I want to show them the best side of their own work. I try to frame each scene as it should be framed, and explore at a speed that lets the ambient detail flourish. I try to behave as my character would behave, and give due reverence to incidental dialogue rather than hurrying through to an event trigger. I want to entertain the onlooker, to catch them in their own net, to reassure them that it was all worth it. Look at this amazing thing you’ve made! See how it sings and dances even in my clumsy fingers. Marvel at the gentler or at least, more coherent and purposeful reality you’ve hacked and conjured from the random matter of this hurtling, aimless planet. Please don’t fixate on the fact that I’ve missed a cue somewhere and spent 15 minutes trying to open a single door. I try to play this way as much for the effect on myself, as for the developer concerned, who may or may not be tapping their feet, waiting for me to amble out of the tutorial area. Being careful of others is a form of self-care. Bea played games for me too during her illness, letting me into her own performances of universes I lacked the time for or was dismissive of. She showed me the far peaks of Horizon: Zero Dawn and the incredible lategame world reset of Dragon Quest 11, a game I introduced her to mostly because I found the voice-acting comic. She walked me across the border to Mexico in Red Dead Redemption 2, another gargantuan quest-a-thon I discarded a few hours in. She showed me the underside of Mario Sunshine, and talked me through her decisions in XCOM, having overcome her dislike of a game that kills people off without ceremony or hope of retrieval. All these experiences were fleeting and relatively insignificant parts of our lives together, but they were acts of kindness that will never leave me, and for that, Bea, I am thankful.