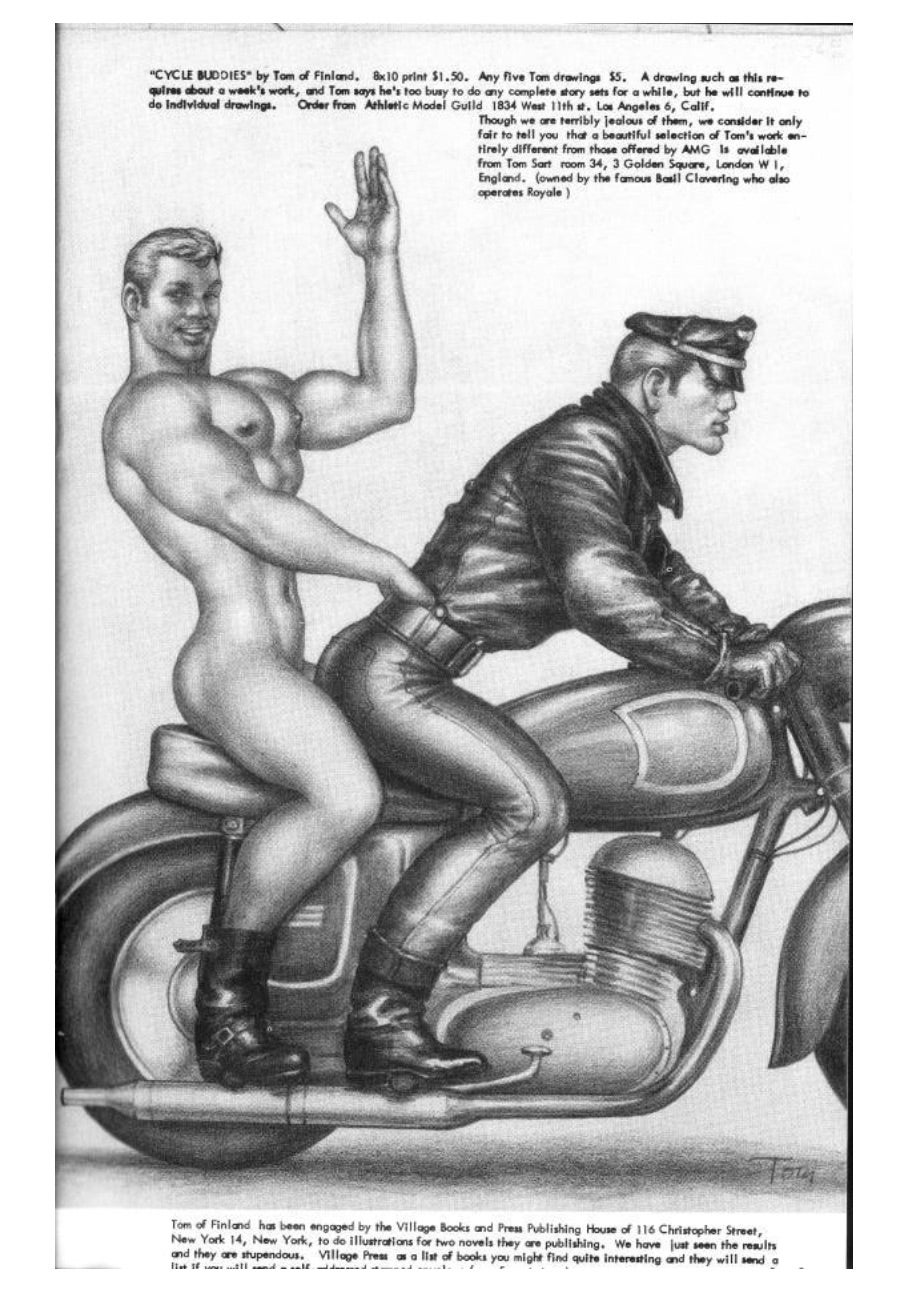

In 2010, on a borrowed computer in a college friend’s bedroom in Boston, I fell for my first videogame character. Alistair from Dragon Age: Origins was charming, funny, disarmingly oblivious, and hot. He had interesting thoughts about the world, tragedy and trauma to live with, and a vision of what the future should look like. He looked sexy in over-the-top pauldrons. And like every one of my teenage crushes, he was straight. Unlike in real life, I wasn’t limited to just nodding morosely and moving on — or like on one memorable occasion, sobbing passionately into my best-friend’s pillow — because the power of gay, internet horniness came to my rescue. Randy, technoliterate gaymers soon released mods turning the various romanceable NPCs in Dragon Age: Origins bisexual, including the himbo Grey Warden of my dreams. Finally, my hours of complimenting Alistair and offering him little presents would result in the much-desired gay sex scene. A win for my nineteen-year-old spank bank. When I mention stories like that to my ex-husband, he usually gives a good-natured groan and says something along the lines of, “Sharang, internet porn exists!”. He’s right of course. Be it via HBO, PornHub, or some of the excellent porn film festivals that take place annually (I highly recommend them), there’s no dearth of titillating material available for our consumption. But it’s not just about that is it? While hot-and-heavy porn is all very well for a quick fix, it’s the human narratives behind the sex that provide the most satisfying stimulation. I think about the works of seminal pornographic artist Touko Valio Laaksonen, better known as Tom of Finland, whose explicit drawings of muscle-bound leather-men helped shape how we view gayness and masculinity in society today. Laaksonen’s artistic world isn’t just one of balls, butts, and dicks, but of leather bikers, gay police officers, and dominant, uniformed soldiers, of the erotic potential of the before and the after. In their essay in Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian and Queer Essays on Popular Culture, artist Nayland Blake discusses Laaksonen’s work in loving detail: “Narrative opens up the image,” they claim. “This is a world we recognise, but without the boundaries on our desires.” This recognition of Laaksonen’s world, of situating his characters within a milieu we recognise and within which we can imagine stories, while perhaps not key to Laaksonen’s art, nevertheless contributes immensely to our appreciation of it. So it’s not a mere desire to get off that fuels the fan-shipping of presumably straight characters, often referred to as “slash”. Slash, Henry Jenkins writes in his influential book Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, “breaks…with the commodification of pornography, offering erotic images that originate in a social context of intimacy and sharing.” It’s not just any videogame warrior I wanted to bang, it was the goofy guy I’d bantered with, killed Darkspawn with, grown to understand and admire. It was a fantasy of romance, not just sex. Romance as a genre has a complicated and contentious history, of course. At the last GDC I attended, I listened to multiple presentations on how videogame romances in mainstream titles propagate poor ideas about how real relationships should and do function. In the fiction world, romance — and by extension, the romance readership — is often derided and scorned. Many scholars argue that the miasma of disdain that seems to surround the genre stems from longstanding misogyny and our collective distaste for women’s pleasure. But as Caily Hall reminds us in her LA Review of Books essay The Consolation of Genre: On Reading Romance Novels, romantic stories “help readers keep engaging in the very real work of opposition”. This idea of “opposition to the norm” might be even more true for videogames than for romance novels (which form the focus of Hall’s essay). To designer Katelyn Campbell, the very act of modding, of tinkering with a game’s source code in order to add queer content, is a form of queer rebellion. In her essay in First Person Scholar, Campbell argues that the creation of queer mods “challenge the developer’s authority and even authorship…challenging their authority and ability to regulate queerness out of games or define queerness on their terms. Through acting directly on a game’s source materials, these modders are putting queerness exactly where the industry often insists it is not wanted and therefore cannot be.” As a sort of fuck you to sanitised, corporatised, lawyer-approved depictions of queerness, these modders announce, “This is how we’re queer!”. Nowhere is the casual and gleeful abandonment of a game’s original intent more apparent than in the fanfiction community. On fanfiction behemoth website Archive of Our Own, we find stories of Alistair anxious that the erotic pleasure he gets from hurting elf-assassin Zevran goes against his faith, tales of Zagreus from Supergiant’s Hades stumbling upon Achilles and Patroclus having sex and then joyfully joining them in a threesome, and works with helpfully descriptive titles like Captain Falcon Pounds Wario’s Fartbox (at least 21 people have given that one a like, or a “kudos” to use AO3’s lingo). To the fanfiction community, as long as it’s well-labelled, no scenario is too taboo. And more than just provide titillation, fan-created works “can also let writers, and readers, ask and answer speculative and reflective questions about our own lives, in a way that might get others to pay attention,” as Stephanie Burt notes in The New Yorker. Whether they mean to or not, all artists and writers infuse their work with their politics, their struggles, their assumptions, and their hopes. Games, as an intensely participatory medium, perhaps betray their creators’ ideas more readily than other media: players don’t just view or read games, they move within them, tinker them, experience them with all their senses. As such, the fan creations that come out of games can be particularly potent and particularly meaningful to their creators. Gita Jackson describes how the fanfiction writing community around Detroit: Become Human coalesces not around expanding a beloved story, but fixing it. “Fans seem to want to expand upon the text not because they think it’s good, but because they think it’s bad,” she writes, noting how Connor and Hank seem to have unmistakable sexual and romantic chemistry that the game simply fails to explore. Enthusiastic fans itch to explore it themselves. Game designer and scholar Robert Yang eloquently describes how his mod to turn Alistair bisexual — possibly the very same mod I discovered as a thirsty undergrad — turned Dragon Age: Origins into a tragic commentary on the difficulties surrounding gay marriage. Yang, the creator of the mod, seems to lose control of his own creation; what he hoped would be a lovely romance turned into something else entirely, when he discovered that he still couldn’t marry Alistair at the conclusion of the story: “I realized: this relationship was doomed from the start, from my very first choice to inhabit a male player character. Even using mods or hacks would never change this crucial consequence of the story: Alistair must have children, but I will never be able to provide him with one because I don’t have a vagina.” If that doesn’t illuminate something about contemporary queer politics, I’m not sure what will. In a sense, every act of gaming is an act of fan creation. Each player creates their own version of the story, something unique to their playstyle and rhythms. Watching a streamed game can be seen in a sense as reading fanfiction. As Rebecca Carlson writes in her editorial to Volume 2 of the journal Transformative Works and Culture, “social participation and active production — of meanings and experiences as much as of concrete fan-made work — are embedded in all acts of gaming.” And as inevitable as these fan-creations are, perhaps we can draw power from them. Perhaps sharing our queer fantasies can help improve our reality?